RTC + Jenkins: Flow Targets in Continuous Integration

Rational Team Concert from IBM is a big product that provides, among several features, its own Source Control Management system. It’s more complex than git and mostly GUI-oriented (Eclipse-based), though Streams and Components solve many architectural problems in an elegant way. It’s worth trying it out to get another perspective from SCM, and I’ve realized that people either love or hate it, while I often find myself changing sides…

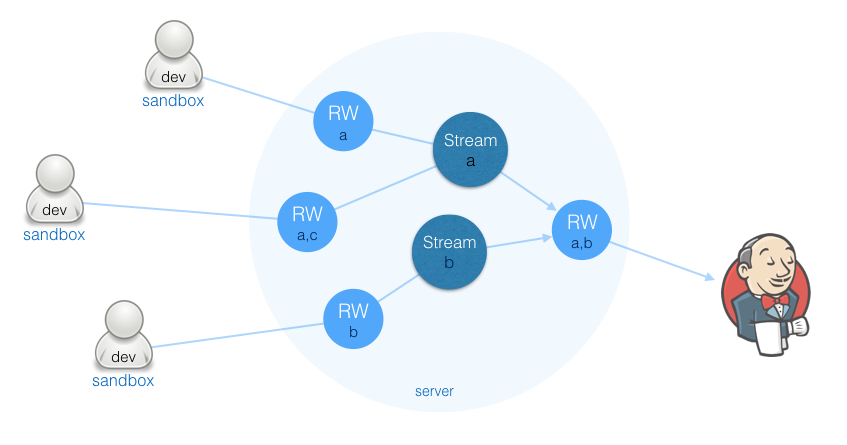

In regular use, there are Streams and Repository Workspaces (RW) – which are the closest equivalent to branches (but not really) – and a mystical thing called Component that basically holds a piece of code and works great to make projects modular, yet keeping the flow between the branches. This multi-dimensional SCM turns out to be powerful if well orchestrated, and after some use it becomes noticeable how easy it is to flow code between branches. Preferences apart, the purpose of this post is to show how this new concept takes place within Continuous Integration.

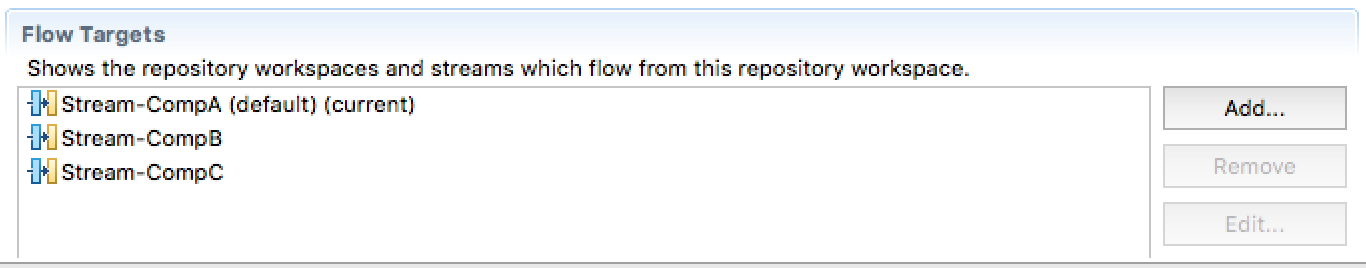

A Flow Target is a link between Streams/RW to denote the destination of the change sets. Two special targets are chosen among them: current and default.

- Current : actual target where change sets are delivered.

- Default : default target for delivery. If the current target is not set also as default, a pop-up window will ask the developer to confirm the delivery.

Developers are free to choose their targets, though only one target can be used at a time. Plus, as seen above, very often there are targets with no labels at all.

But how does this stuff work in Continuous Integration?

How RTC SCM behaves in Continuous Integration – specifically with Jenkins – is still often misunderstood, even among experts. As RTC itself is a full-featured product, mastering all its corners is quite challenging. In order to understand the experiment below, one should be familiar with Streams and Components, Repository Workspaces and flow targets. Although a build environment is necessary for the experiment, knowledge of Team Concert plugin and basic configuration with RTC and Jenkins is a soft requirement.

–

Part 1: Initial Setup and first build.

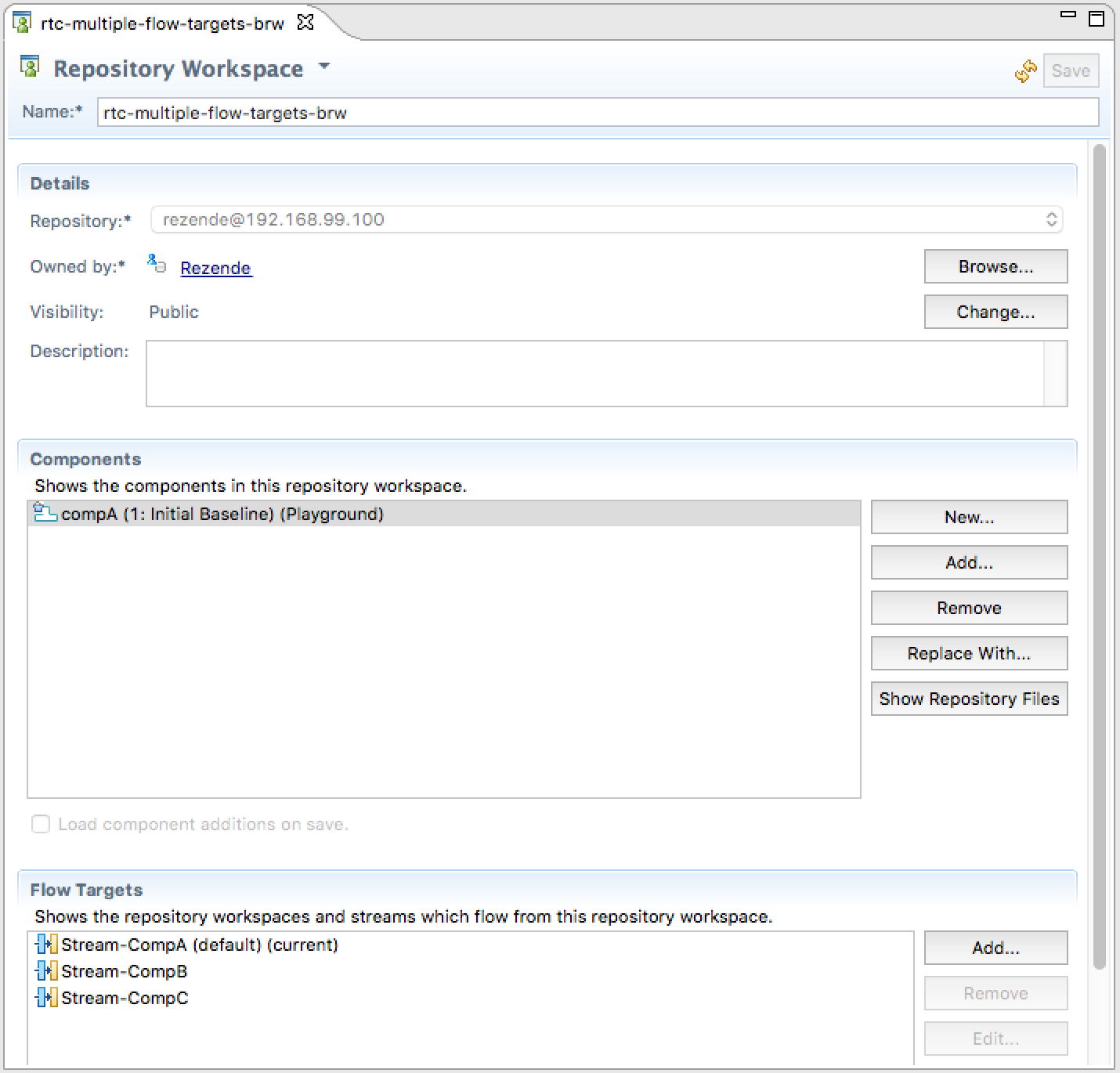

This experiment starts with three Streams (Stream-CompA, Stream-CompB, and Stream-CompC), each containing the respective component compA, compB and compC.

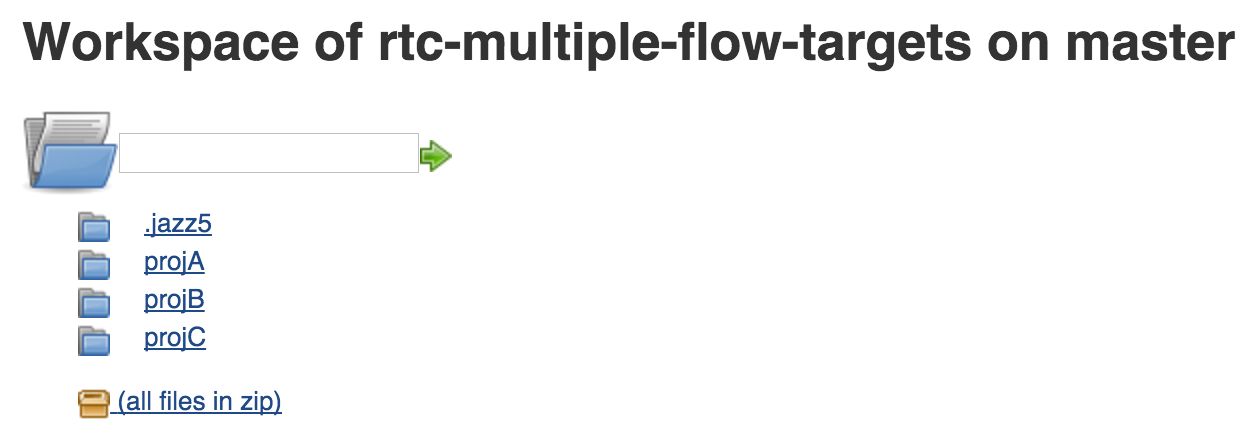

These components, in turn, hold each a single and very simple project, whose root folders are ProjA, ProjB and ProjC.

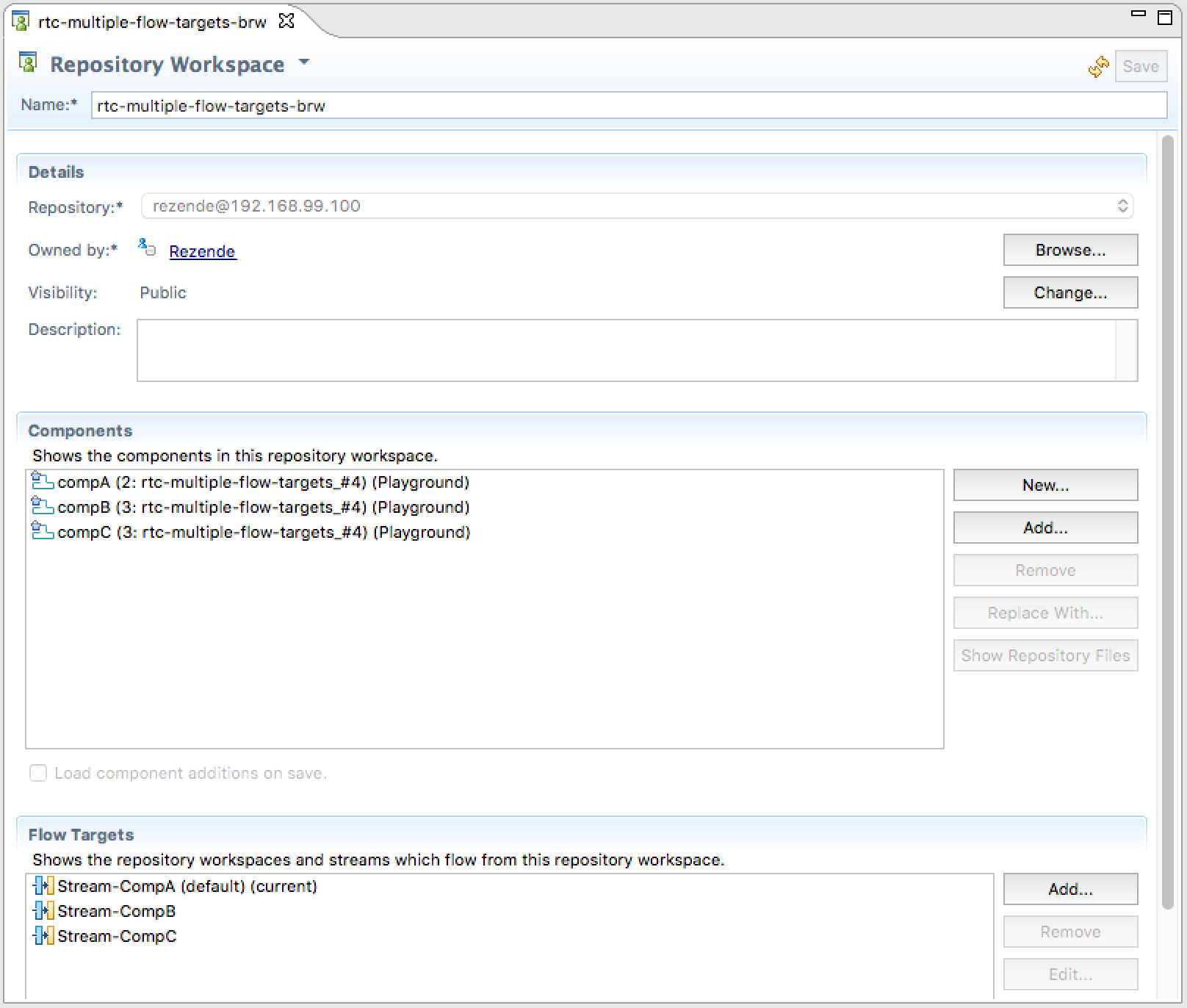

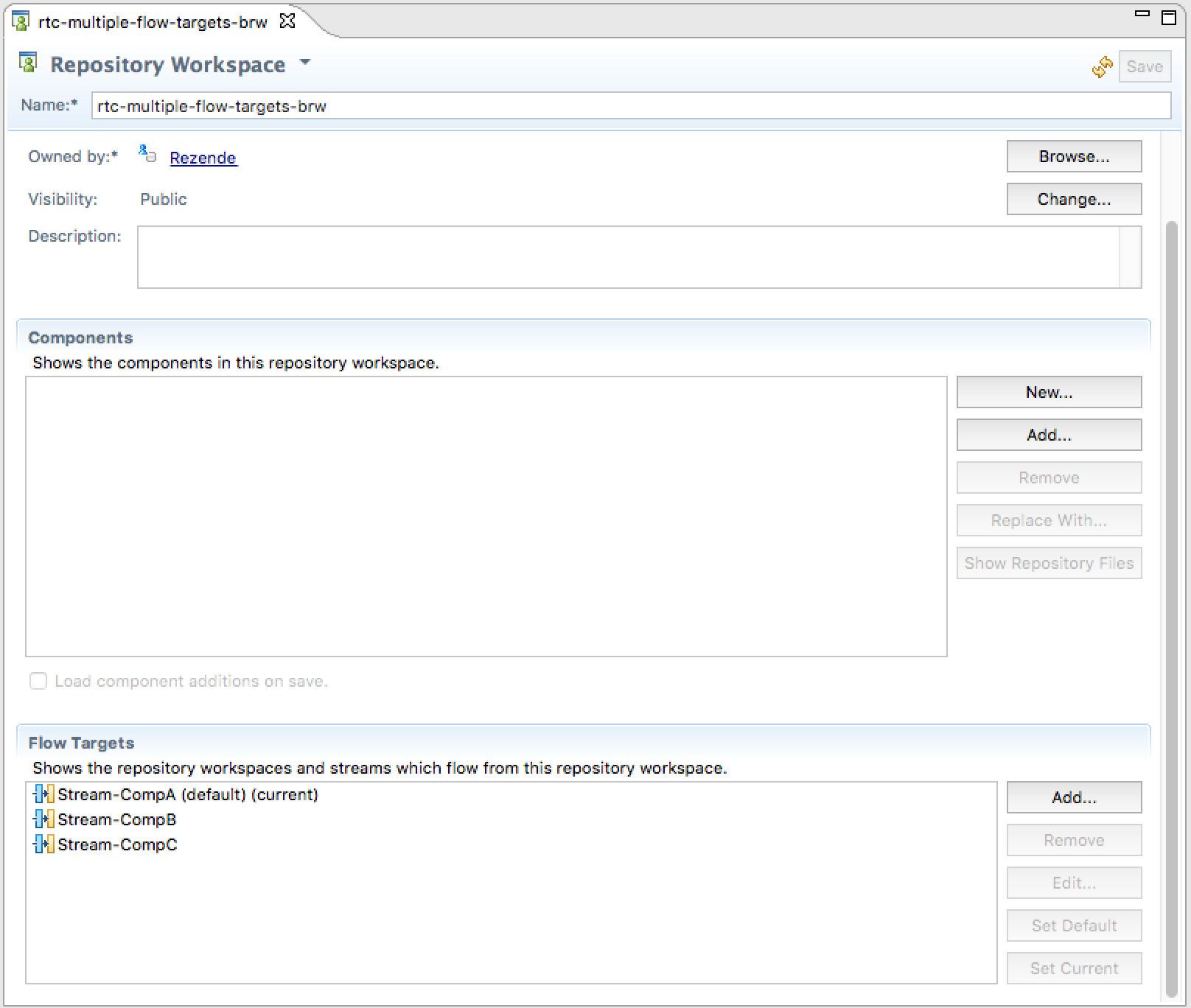

Our Build Repository Workspace (rtc-multiple-flow-targets-brw) initially contains a single component compA, as in Stream-CompA.

Although the Repository Workspace initially holds only one of those components, the first build loads all the three projects into the Jenkins Workspace.

By refreshing the Repository Workspace in the RTC Client, we see that the respective components were automatically included.

Conclusion: The Repository Workspace automatically accepts all the change sets and includes all the missing components, despite the default and current labels.

–

Part 2: Default/Current flow target is deleted. Second build starts.

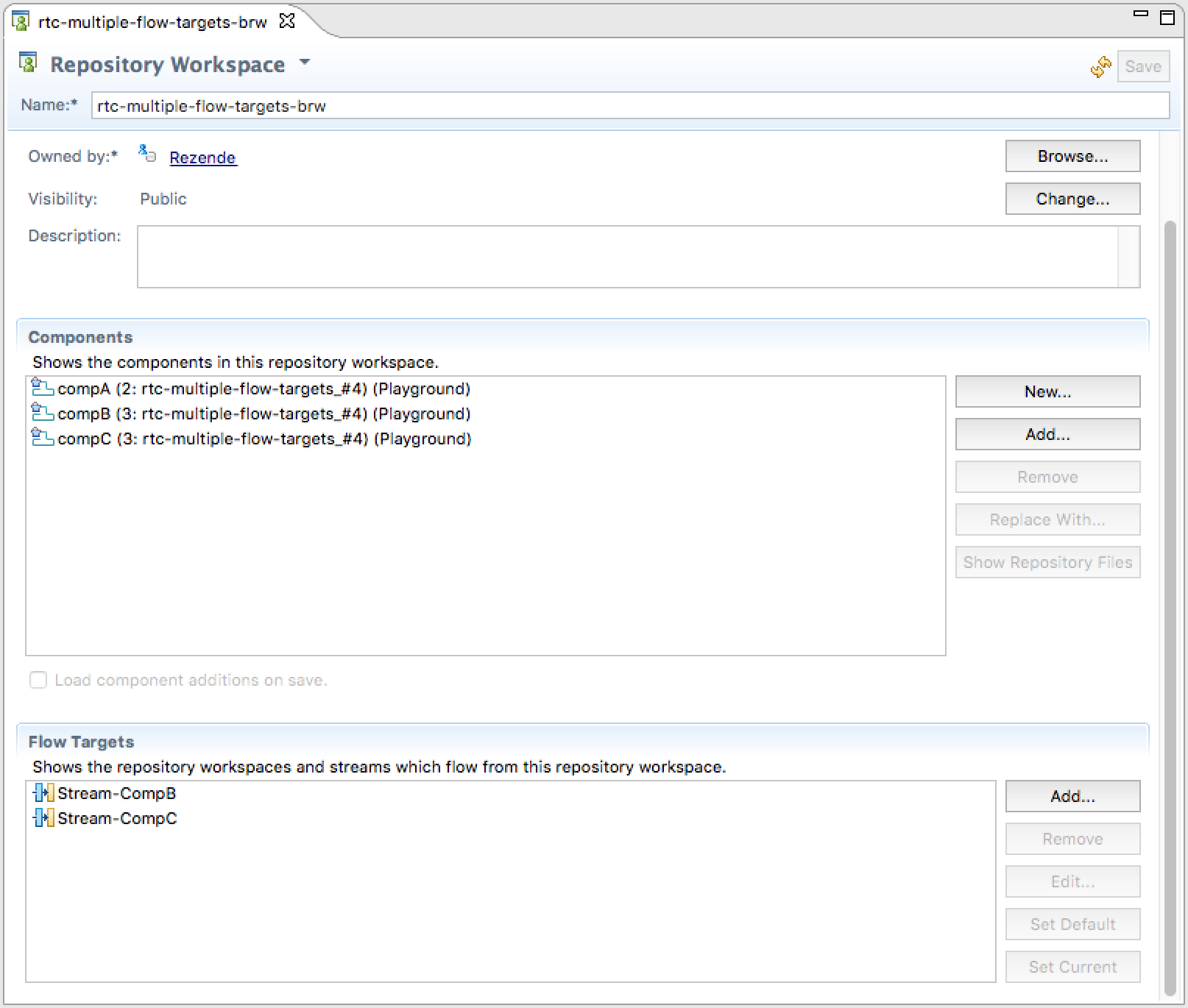

Next, Stream-CompA is removed from the list of flow targets of our Build Repository Workspace. The current configuration leaves no default nor current targets.

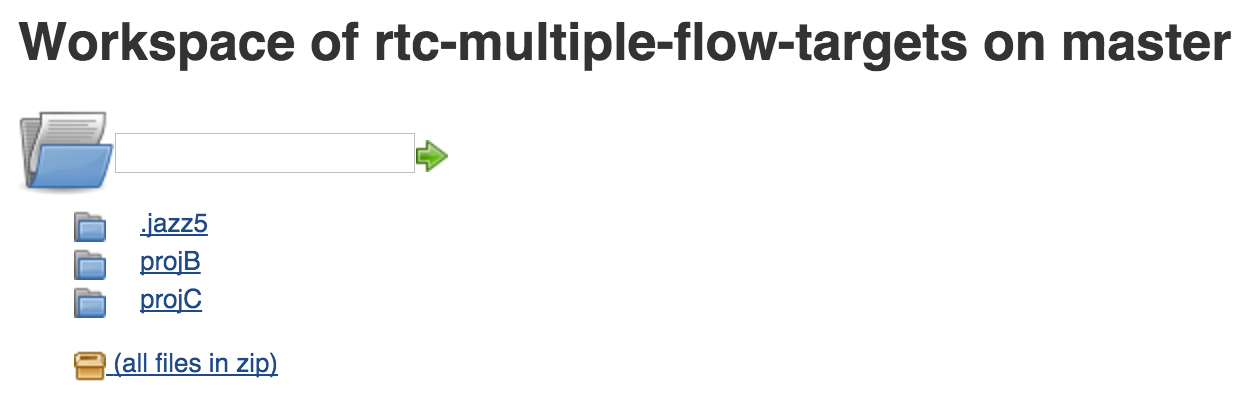

Running the build will load only ProjB and ProjC into Jenkins Workspace.

The compA is automatically excluded from the Repository Workspace.

Conclusion: Components from the Build Repository Workspace are always in sync with those from flow targets. Whether a flow target is added or removed, the respective components will be included or excluded accordingly.

–

Part 3: Two Stream have a component in common. Final build.

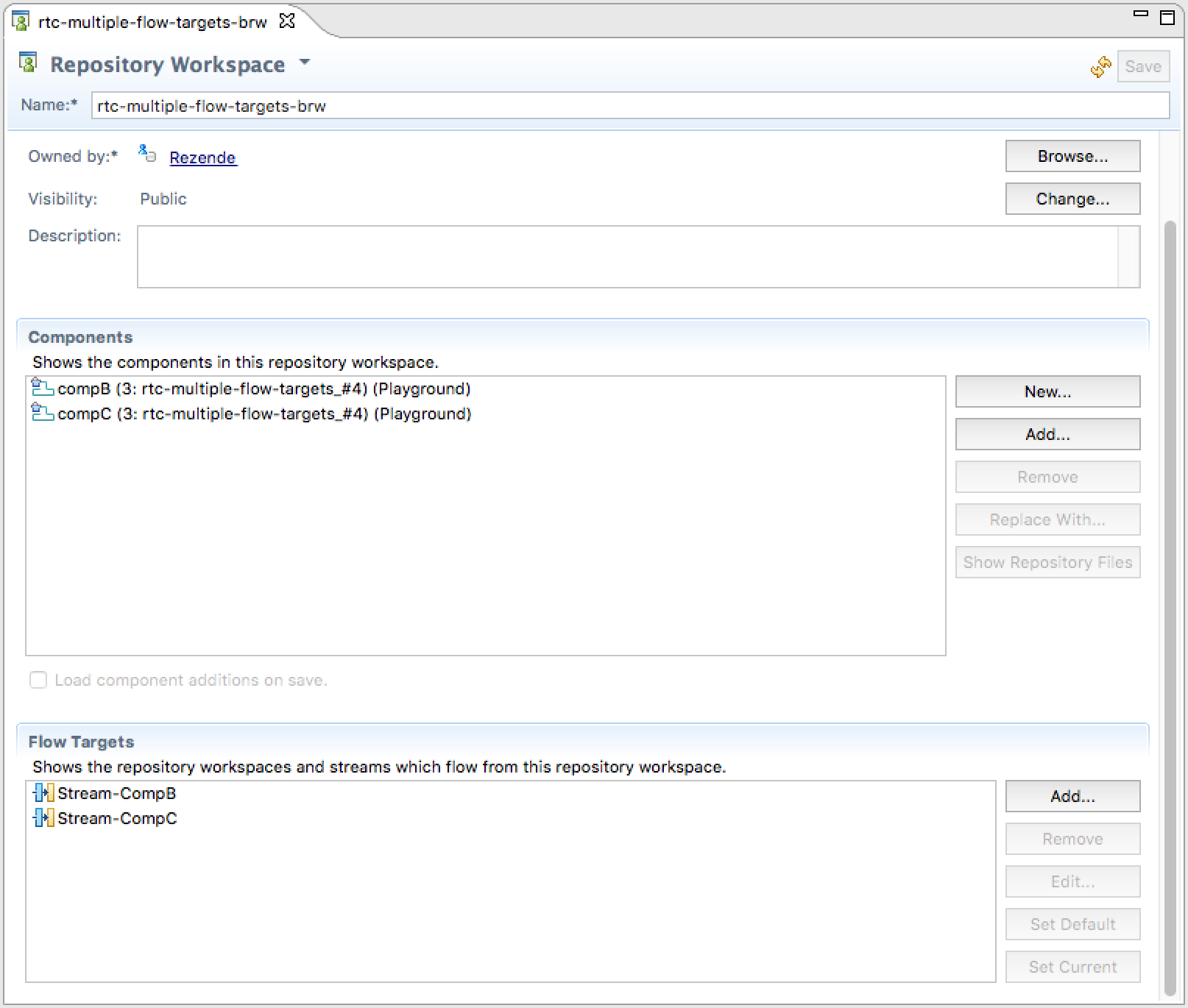

Last, Stream-CompA is added to the flow target list and all components are (manually) removed from the Build Repository Workspace.

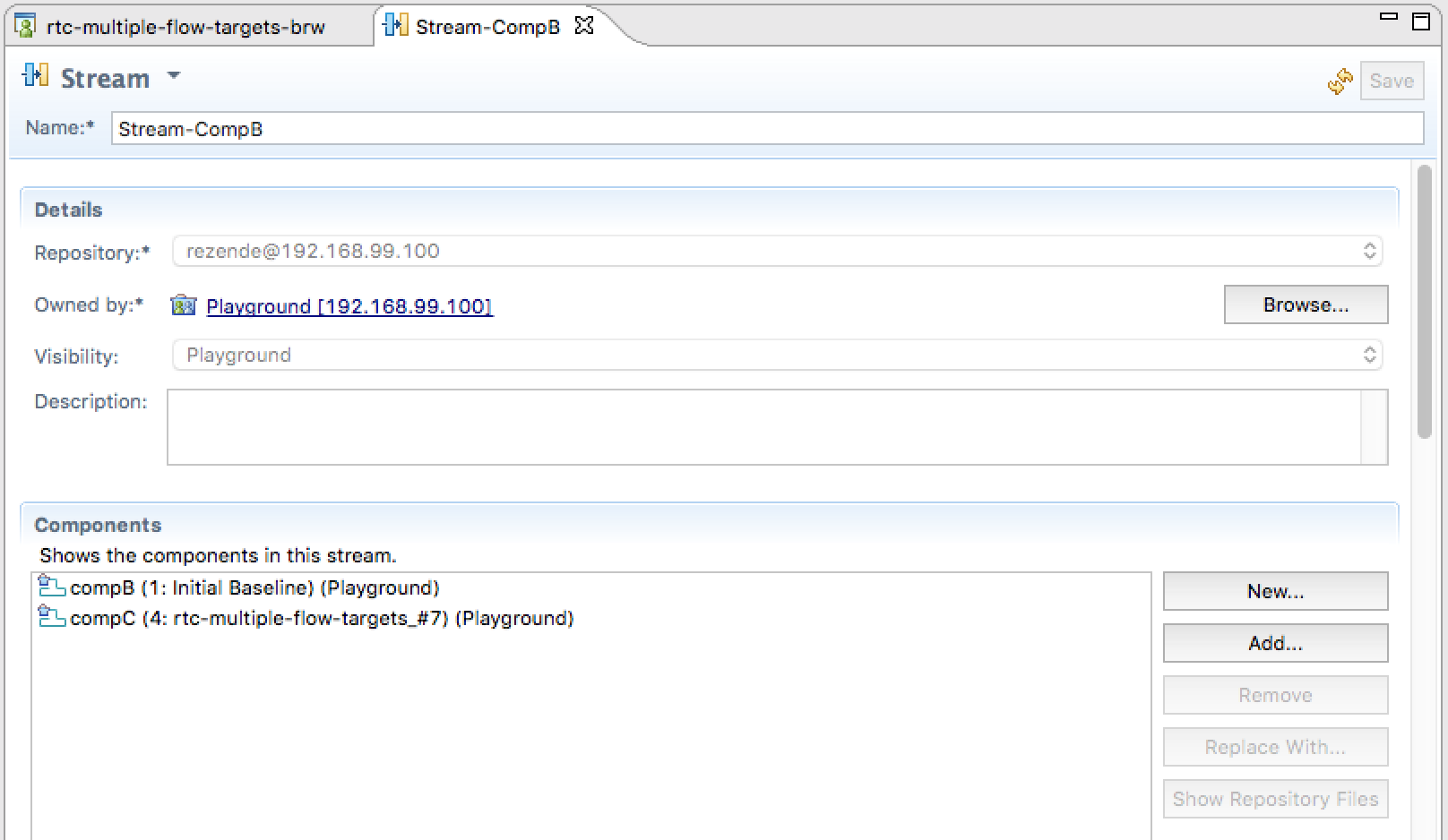

Component compC is added to Stream-CompB.

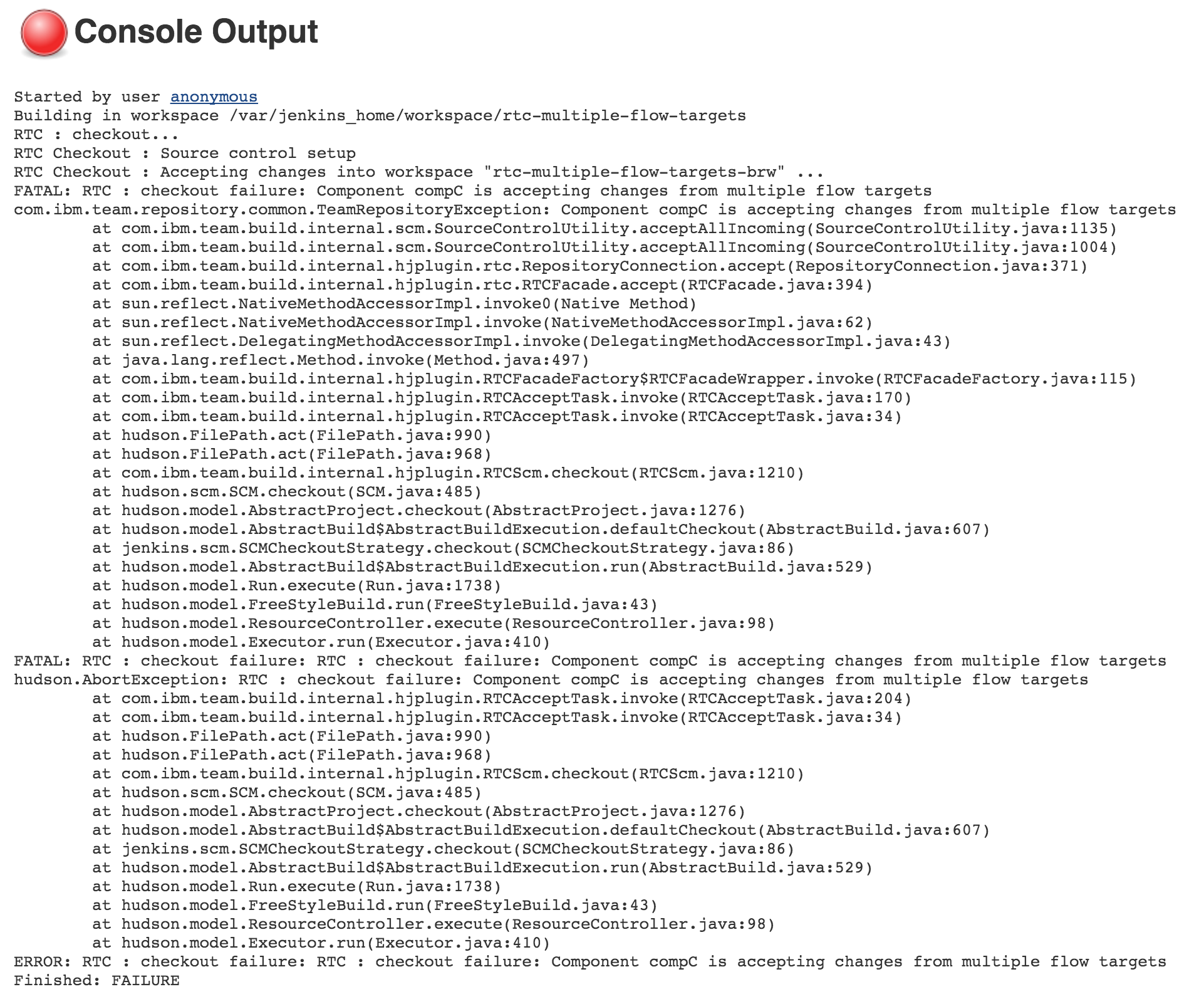

This time the build fails because compC has conflicting sources.

Conclusion: It is critical that every flow target provides exclusive components to the Build Repository Workspace.

–

Conclusion

The boundaries between SCM and Continuous Integration are, in most cases, very well defined. A build environment fetches from a branch (tag, revision, snapshot… you name it), just like a regular user would do. In that sense, CI would be nothing else than a “read-only” user, whose tasks are to pile up snapshots for the build flow, manage the builds, their results, deploy artifacts and many more steps which are pretty much outside the scope of SCM.

With RTC, however, this comparison is not 100% true: the way Jenkins loads the Repository Workspace is significantly different from how it’s done in the RTC Client.

- Every assigned flow target is taken into account, independently of the “default” and “current” settings.

- Repository Workspace’s components are synchronized with flow targets’ components. When components are added or removed from any flow target, these updates are propagated to the RW.

- As consequence, flow targets are not allowed to have components in common.

These properties benefit bigger projects in Continuous Integration. The diagram below illustrates a basic SCM configuration with interface to Jenkins.